Bang / Guns

See other Bang / Guns Articles

Title: Judge Neil Gorsuch: Some Cause for Concern (Stop & Frisk, Disarm)

Source:

Ameican Thinker

URL Source: http://www.americanthinker.com/arti ... ch_some_cause_for_concern.html

Published: Feb 3, 2017

Author: Lawrence D. Pratt and William J. Olson

Post Date: 2017-02-03 15:21:48 by Hondo68

Ping List: *Bang List* Subscribe to *Bang List*

Keywords: None

Views: 34473

Comments: 66

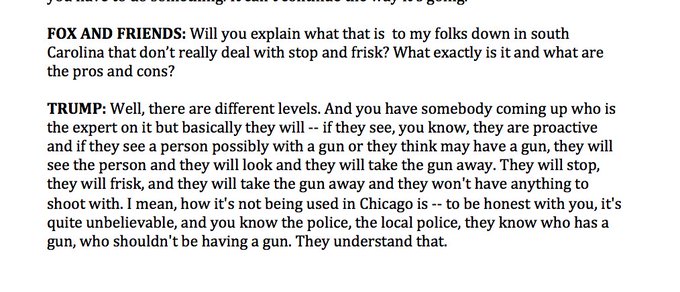

In recent days, news outlets have been reporting that 10th Circuit judge Neil Gorsuch has now risen to the top of President Trump's list of potential Supreme Court nominees. He apparently replaces Judge William Pryor, who was widely reported as previously leading the pack of potential nominees. Judge Pryor faced significant backlash from many on the right, including Evangelical Christians, criticizing Pryor's apparent support of the radical homosexual and transgender agenda. The danger in being the front runner for a spot on the High Court is that you receive intense scrutiny, and, as with most candidates, Judge Gorsuch is difficult to evaluate fully. Having spent some time digging into Judge Gorsuch's background, we have found many good indicators. First, we should say that we personally knew his mother – Anne Gorsuch Burford, a lawyer whom President Reagan appointed in 1981 as director of the Environmental Protection Agency. Anne was both principled and fearless – taking many arrows in her faithful pursuit of President Reagan's environmental agenda. Sadly, the Reagan administration failed to provide her the backing she deserved, leading to her early departure from that position. Judge Gorsuch's distinguished maternal pedigree should not be overlooked. As to Judge Gorsuch's judicial record, he authored the excellent opinion in United States v. Ackerman, 831 F.3d 1292 (10th Cir. 2016), which, in an alternative holding, determined that government accessing a person's emails constitutes a "search" under the revitalized property rights trespass test articulated by Justice Scalia in the case of United States v. Jones, 132 S.Ct. 945 (2012). Additionally, Judge Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion in the 10th Circuit, in what became the Hobby Lobby case in the U.S. Supreme Court, determining that the religious freedom of Christian businesses trumps the "right" of a woman to have her employer subsidize the killing of her unborn baby. Finally, Judge Gorsuch is a vocal critic of the modern "Administrative State" – advocating the elimination of the doctrine of "Chevron deferense," which has given unelected and unaccountable federal bureaucrats vast and unconstitutional power over just about every aspect of our lives. On the other hand, there is reason for pause with Judge Gorsuch's record. Judge Gorsuch joined in one opinion, United States v. Rodriguez, 739 F.3d 481 (11th Cir. 2013), which causes us to have some concern about his understanding of the relationship between the government and an armed citizenry. To be fair, Judge Gorsuch did not write the Rodriguez opinion – his colleague, Judge Bobby Baldock, was the author. Nevertheless, Judge Gorsuch joined the opinion. He could have filed a principled dissenting opinion, or even a concurring opinion agreeing only in the judgment. The facts of the case are these. A New Mexico policeman observed Mr. Rodriguez, a convenience store clerk, carrying a concealed handgun. Carrying a concealed loaded handgun is illegal in New Mexico without a permit but legal if one has a license to do so. The officer, upon seeing a Rodriguez's handgun, detained him, then – acting first and asking questions later – forcibly disarmed Rodriguez. After finding out that Rodriguez did not, in fact, have a license to carry and, indeed, was a convicted felon, the officer placed him under arrest. Of course, hard cases make bad law. But the precedent from the Rodriguez opinion will affect police-citizen relations in New Mexico, and possibly elsewhere in the Tenth Circuit, for many years to come. Not bothering to figure out the legality of Rodriguez's firearm before detaining and disarming him, the officer's initial actions would have been the same even if Mr. Rodriguez had been a lawful gun owner. According to the 10th Circuit's opinion, the police are justified in forcibly disarming every armed citizen based on nothing more than the presence of a concealed firearm. This allows the police to treat every law-abiding gun owner like a criminal – which, in many cases we have seen, includes rough treatment such as grabbing him, twisting his arm behind his back, slamming him down on the ground, and handcuffing him. Far too many police officers do not like anyone to be armed other than themselves and have taken it upon themselves to intimidate those who dare to exercise Second Amendment rights. Under the Rodriguez decision, only after being forcibly disarmed and detained would a citizen be entitled to demonstrate that he was lawfully exercising his Second Amendment rights. The Circuit Court based this decision on Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) – the "stop and frisk" doctrine. One of the holdings from Terry is that, if the police have "reasonable suspicion" that a person is both "armed and dangerous," they can temporarily seize his weapon to keep everyone safe. Of course, anyone with a smidgeon of common sense knows that just being an "armed" law-abiding citizen does not also make a person "dangerous" any more than a police officer with a gun should be considered dangerous. Unfortunately, the Rodriguez opinion allows the police to conflate the two concepts and treat all armed persons as if they were automatically dangerous. According to the panel opinion joined by Judge Gorsuch, the mere presence of a loaded concealed firearm "alone is enough to justify [the officer's] action in removing the handgun from Defendant's waistband for the protection of himself and others." To be sure, Rodriguez did not raise a Second Amendment claim before the court, and the court cited various Fourth Amendment cases to justify its bad decision. But judges cannot completely hide behind precedent. Judge Gorsuch was free to express his disagreements with those precedents, even if he felt obliged to concur in the result. But that is not what he did. Instead, the court went so far as to quote Justice John Marshall Harlan II in Terry for the pre-Heller assertion that "'concealed weapons create an immediate and severe danger to the public.'" Is that what Judge Gorsuch thinks of the 14.5 million law-abiding Americans with concealed carry permits? That they are an immediate and severe danger to the public? Fortunately, the Framers disagreed, emphasizing in the Second Amendment that an armed populace is not only beneficial to, but indeed "necessary to" the preservation of a "free state." Unfortunately, in almost all of the countries of the world, the government considers an armed citizen a threat. But in the United States, the police should consider an armed citizenry one of the sources of strength of the nation. It is hard to imagine a better way to discourage law-abiding people from carrying guns than to do what the 10th Circuit did, and sanction the police forcibly disarming anyone seen carrying a gun. At the end of the day, a single opinion such as this is not be enough to derail a Supreme Court nomination, especially since Judge Gorsuch did not even write the opinion. But he certainly did join the opinion. And if he is nominated to the High Court, a pro-gun United States senator or two should most certainly inquire as to this decision and ask Judge Gorsuch to explain whether he really believes that the police should be free to treat all armed citizens as though they were dangerous criminals. Lawrence D. Pratt is executive director emeritus of Gun Owners of America. Twitter: https://twitter.com/larrypratt. William J. Olson is an attorney in private practice in Virginia with William J. Olson, P.C. and represents Gun Owners Foundation. Twitter: https://twitter.com/Olsonlaw. Poster Comment: Gorsuck is close to Trump's stance of Stop, Frisk & Confiscate guns. http://hotair.com/archives/2016/09/22/trump-stop-frisk-great-way-cops-seize-guns/

Post Comment Private Reply Ignore Thread

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

Begin Trace Mode for Comment # 38.

#1. To: hondo68, GrandIsland (#0)

The facts of the case are these. A New Mexico policeman observed Mr. Rodriguez, a convenience store clerk, carrying a concealed handgun. Carrying a concealed loaded handgun is illegal in New Mexico without a permit but legal if one has a license to do so. The officer, upon seeing a Rodriguez's handgun, detained him, then – acting first and asking questions later – forcibly disarmed Rodriguez. After finding out that Rodriguez did not, in fact, have a license to carry and, indeed, was a convicted felon, the officer placed him under arrest. Further, Rather than accept the yellow journalism characterism of the court opinion in Rodriguez, it is preferable to review the actual opinion. Taking the second quote first, I would ask which part of the Second Amendment protects the right of a convicted felon to keep and bear a concealed stolen weapon? The yellow journalists are adequately addressed by the actual court opinion. http://lawofselfdefense.com/law_case/us-v-rodriguez-739-f-3d-481-10th-ct-app-2013/ State: United States v. Rodriguez, 739 F.3d 481 (10th Ct. App. 2013) United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit December 31, 2013, Filed No. 12-2203Reporter 739 F.3d 481 * | 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 25853 ** | 2013 WL 6851128 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff – Appellee, v. DANIEL MANUEL RODRIGUEZ, Defendant – Appellant. Counsel: Scott M. Davidson, The Appellate Law Office of Scott M. Davidson, Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Defendant-Appellant. James R. W. Braun, Assistant United States Attorney (Kenneth J. Gonzales, United States Attorney, with him on the brief), Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Plaintiff-Appellee. Judges: Before GORSUCH and BALDOCK, Circuit Judges, and JACKSON, District Judge. Opinion by: BALDOCK Section 30-7-1 of the New Mexico Criminal Code defines “[c]arrying a deadly weapon” as “being armed with a deadly weapon by having it on the person, or in close proximity thereto, so that the weapon is readily accessible for use.” Section 30-7-2 of the Code is entitled “Unlawful carrying of a deadly weapon.” Subject to five enumerated exceptions, subsection (A) proscribes “carrying a concealed loaded firearm or any other type of deadly weapon anywhere[.]” N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-2(A). The issue presented in this appeal is whether a police officer who observes a handgun tucked in the waistband underneath the shirt of a convenience store employee has reasonable suspicion that the employee is unlawfully carrying a deadly weapon in violation of § 30-7-2(A), in turn justifying a “stop and frisk.” The answer is yes. I. We succinctly state the relevant facts. Around 6:00 p.m. on July 27, 2011, Albuquerque Police Officer Frank Munoz responded to a dispatch informing him that two employees of the “Pit Stop” convenience store and gas station, located at 6102 Central Avenue SW in a reportedly “high crime” area, were showing each other handguns. Tr. vol. 3, at 8, 44. Fellow Officer Steven Miller also responded to the dispatch. Officer Munoz described the store as being “pretty small on the inside.” Id. at 13. Upon entering the store, Officer Munoz, accompanied by Officer Miller, observed Defendant Daniel Rodriguez a “couple feet away” stocking shelves. Id. at 14. As Defendant bent over, Officer Munoz noticed a silver handgun tucked in the back waistband of his pants. Defendant’s shirt concealed the handgun when he stood upright. Officer Munoz told Defendant, “Let me see your hands, and let’s step outside.” Id. at 51. At the suppression hearing, Officer Munoz testified: [Defendant] asked us what for, “What did I do?” And since we were in a pretty cramped area when we walked in, I didn’t want myself and Officer Miller or [Defendant], all of us, to be in that cramped area in case anything occurred, so I told him, “Let’s step outside,” and that I needed to ask him a question. He was a little upset and wanted to know what he had done. I told him to step outside. He then went past myself and Officer Miller to the door. As he pushed the door open once again his shirt came up, and I saw the gun, and it was at that time I pulled the gun out of the back of his waistband. Id. at 16. When asked why he removed the gun from Defendant’s waistband, Officer Munoz stated, “Just for officer safety, until we could figure out what was going on and why he had a firearm.” Id. Outside the store, Officer Munoz promptly asked Defendant why he was concealing a handgun. Defendant responded that “somebody had shot at him at that same location at the gas station.” Id. at 25. Officer Munoz asked Defendant whether he had a permit to carry the handgun. Defendant said he did not. Officer Munoz instructed Defendant to turn around and place ]his hands in the frisk position on a nearby truck. Visible tattoos on Defendant’s legs prompted Officer Munoz, a former prison guard, to ask Defendant if he had been arrested. Defendant stated he recently had been released from prison. Following an unremarkable “pat search” of Defendant, Officer Munoz permitted him to sit on the curb and smoke a cigarette. Id. at 19. A federal grand jury charged Defendant with one count of being a felon in possession of a firearm and ammunition in violation of 18 U.S.C. §§ 922(g)(1) and 924(a)(2). Defendant filed a motion to suppress evidence, claiming a number of constitutional violations arising out of the foregoing incident. The district court denied his motion in a lengthy opinion. United States v. Rodriguez, 836 F. Supp. 2d 1258 (D.N.M. 2011). Defendant subsequently entered a conditional] plea of guilty pursuant to Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(a)(2). After the court sentenced him to 30-months imprisonment, Defendant appealed only his Fourth Amendment claims that Officer Munoz unreasonably seized him and removed the handgun from his waistband. According to Defendant, “[p]ossession of a concealed firearm in the State of New Mexico, standing alone, cannot be the basis for the type of investigative detention and weapons seizure that [he] was subjected to.” Def’s Op. Br. at 15. Notably, Defendant does not dispute the district court’s findings, which are consistent with our recitation of the facts. The only question for us is whether the law as applied to those facts supports Defendant’s claim that Officer Munoz violated his Fourth Amendment rights. We review de novo the district court’s determination that the officer’s actions were reasonable within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. See Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690, 699, 116 S. Ct. 1657, 134 L. Ed. 2d 911 (1996). Exercising jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291, we affirm. [...] B. At the commencement of their encounter, Officer Munoz knew Defendant was carrying a concealed handgun in his back waistband. Officer Munoz saw the handgun because Defendant was bending over stocking shelves. The only express element of the crime of unlawfully carrying a deadly weapon, as defined in N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-2(A), that Officer Munoz lacked personal knowledge of bore upon the handgun’s condition. Was the gun loaded or unloaded? See N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-2(B) (carrying an unloaded firearm does not violate § 30-7-2(A)). But Officer Munoz did not have to be certain the handgun was loaded to justify Defendant’s seizure; he only had to reasonably suspect the gun was loaded. See Terry, 392 U.S. at 27. “Probable cause does not require the same type of specific evidence of each element of the offense as would be needed to support a conviction.” Adams v. Williams, 407 U.S. 143, 149, 92 S. Ct. 1921, 32 L. Ed. 2d 612 (1972). Necessarily then, neither does the less demanding standard of reasonable suspicion require such evidence. A prudent officer under the circumstances confronting Officer Munoz could reasonably suspect Defendant’s handgun was loaded rather than waiting to find out, thus providing the officer all the suspicion he needed to seize Defendant based on a violation of § 30-7-2(A). One of the basic rules of gun safety promulgated worldwide is to “[a]ssume every gun to be loaded . . . and treat it accordingly.” Int’l Hunter Educ. Ass’n, Firearm Safety: Basic Safety Rules, homestudy.ihea.com/firearmssafety/01actt.htm (visited December 12, 2013). Moreover, that Defendant’s handgun was probably loaded is simply a “common sense conclusion[] about human behavior” that Officer Munoz reasonably could draw from the fact Defendant sought to conceal the gun on his person. Cortez, 449 U.S. at 418. (Defendant has never suggested he was openly carrying the handgun). The principal purpose of carrying a concealed handgun is to assail another or defend oneself. An unloaded firearm serves neither of these purposes well, making the fact that Defendant’s handgun was loaded a distinct possibility. Defendant says that instead of seizing him, Officer Munoz simply should have asked him some questions: [T]he officers would have had a sufficient basis to enter the store and engage [Defendant] in an inquiry as to whether he had permission or a permit for the gun he was carrying. Had [he] either refused to produce a valid permit or admitted to wrongdoing, the officers at that point might have had reasonable suspicion to detain him to investigate the situation further. But in this case, the officers exceeded their authority under the law and seized [his] weapon with[out] a reasonable suspicion that he was engaging in criminal activity and without an articulable basis to believe he was dangerous in any way. Def’s Op. Br. at 34. (internal citation omitted). We disagree. Although Officer Munoz could have sought to engage Defendant in a consensual encounter, the law did not require him to do so—and for good reason. Given the confined space in which the parties found themselves at the outset of their encounter, Officer Munoz exercised sound judgment in declining to question Defendant before detaining him. Officer Munoz explained, “I didn’t want myself and Officer Miller or [Defendant], all of us, to be in that cramped area in case anything occurred[.]” Tr. vol. 3, at 16. No officer reasonably suspecting criminal activity—as Officer Munoz did here—”should have to ask one question and take the risk that the answer might be a bullet.” Terry, 392 U.S. at 33 (Harlan, J., concurring). “The reasonableness of [an] officer’s decision to stop a suspect does not turn on the availability of less intrusive investigatory techniques.” Sokolow, 490 U.S. at 11. “Such a rule would unduly hamper the police’s ability to make swift, on-the-spot decisions . . . and it would require courts to indulge in unrealistic second-guessing.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). What Defendant effectively claims is that the law required Officer Munoz to inquire into the applicability of § 30-7-2(A)’s exceptions before seizing him. Of course, Officer Munoz did not know at the outset of their encounter whether Defendant was “in possession of a valid concealed handgun license.” N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-2(A)(5). Nor did Officer Munoz know whether Defendant was “an owner, lessee, tenant or licensee” of the convenience store. Id. § 30-7-2(A)(1). That New Mexico excepts certain acts or classes of individuals from a law that bans the carrying of a concealed loaded firearm, however, did not negate Officer Munoz’s reasonable suspicion that Defendant’s possession of a concealed handgun was unlawful. See Reid, 448 U.S. at 441 (recognizing that “wholly lawful conduct” may give rise to reasonable suspicion). Neither of these exceptions to § 30-7-2(A)’s prohibition was readily apparent when Officer Munoz seized Defendant. Officer Munoz had no affirmative obligation prior to seizing Defendant—at the risk of harm to himself and others—to inquire of him whether his possession of the handgun fell within the classes excepted by the statute. Cf. Gatlin, 613 F.3d at 378 (“[U]nder Delaware law, carrying a concealed handgun is a crime to which possessing a valid license is an affirmative defense, and an officer can presume a subject’s possession is not lawful until proven otherwise.”). In the end, Defendant grasps at straws. He says the question of whether an officer may conduct an investigative detention based “solely” on the presence of a concealed firearm “is analogous to the question of whether an officer can pull over any motor vehicle he chooses in order to determine whether the driver is properly licensed and in lawful possession of the car.” Def’s Op. Br. at 27. We think not. To be sure, any construction of a motor vehicle statute permitting such random stops, however the statute is worded, would be unconstitutional. In Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U.S. 648, 99 S. Ct. 1391, 59 L. Ed. 2d 660 (1979), the Supreme Court held the Fourth Amendment prohibits an officer from stopping a vehicle for the sole purpose of checking the driver’s license and registration, where neither probable cause nor reasonable suspicion exists to believe the motorist is driving the vehicle contrary to the laws governing the operation of motor vehicles. Id. at 650, 663. The Court reasoned: It seems common sense that the percentage of all drivers on the road who are driving without a license is very small and that the number of licensed drivers who will be stopped in order to find one unlicensed operator will be large indeed. The contribution to highway safety made by discretionary stops selected from among drivers generally will therefore be marginal at best. . . . In terms of actually discovering unlicensed drivers or deterring them from driving, the spot check does not appear sufficiently productive to qualify as a reasonable law enforcement practice under the Fourth Amendment. Id. at 659-60. Driving a car, however, is not like carrying a concealed handgun. Driving a vehicle is an open activity; concealing a handgun is a clandestine act. Because by definition an officer cannot see a properly concealed handgun, he cannot randomly stop those individuals carrying such weapon. Officer Munoz responded to a dispatch reporting two employees of the convenience store were showing each other handguns. Once at the store, he witnessed Defendant carrying the concealed weapon only because Defendant was bending over and his shirt was untucked. Moreover, unlike the random stop of a motorist, we may safely assume the contribution to public safety made by the stop of an individual known to be carrying a concealed handgun will hardly be insignificant since “[c]oncealed weapons create an immediate and severe danger to the public.” Terry, 392 U.S. at 31 (Harlan, J., concurring). Randomly stopping a vehicle to check the driver’s license and registration is more comparable to randomly stopping an individual openly carrying a handgun (which incidentally is lawful in New Mexico). The Supreme Court held the former unconstitutional. Whether the latter is constitutionally suspect is a question for another day. But where a police officer in New Mexico has personal knowledge that an individual is carrying a concealed handgun, the officer has reasonable suspicion that a violation of N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-2(A) is occurring absent a readily apparent exception to subsection (A)’s prohibition. Accordingly, Officer Munoz’s initial seizure of Defendant was “justified at its inception” and therefore passes Fourth Amendment scrutiny. Terry, 392 U.S. at 22. V. This brings us to the manner in which Officer Munoz carried out Defendant’s seizure. Recall Officer Munoz pulled the gun from Defendant’s waistband as Defendant was going out the door. Once Defendant promptly acknowledged he did not have a license to carry the handgun, Officer Miller ran the check that reported the handgun stolen. Defendant’s sole argument in this regard is that Officer Munoz unlawfully dispossessed him of his handgun as he exited the convenience store which, in turn, permitted Officer Miller to run a check of the gun. See Adams, 407 U.S. at 145 (analyzing as a Terry search defendant’s contention that the initial seizure of his pistol, upon which the subsequent search rested, was unlawful). “[T]o proceed from a stop to a frisk, the police officer must reasonably suspect that the person stopped is armed and dangerous.” Johnson, 555 U.S. at 326-27. Defendant acknowledges he was armed, but claims Officer Munoz had no reason to believe he was dangerous. We have already observed that a prudent officer could reasonably suspect Defendant’s handgun was loaded. That alone is enough to justify Officer Munoz’s action in removing the handgun from Defendant’s waistband for the protection of himself and others. But even if Defendant’s handgun had not been loaded, the Supreme Court’s decision in McLaughlin v. United States, 476 U.S. 16, 106 S. Ct. 1677, 90 L. Ed. 2d 15 (1986), forecloses his argument that the gun posed no immediate threat to the officers. In McLaughlin, the Court explained an unloaded handgun is a “dangerous weapon:” [A] gun is an article that is typically and characteristically dangerous; the use for which it is manufactured and sold is a dangerous one, and the law reasonably may presume that such an article is always dangerous even though it may not be armed at a particular time or place. Id. at 17. We will not deny an officer making a lawful investigatory stop the ability to protect himself from an armed suspect whose propensities are unknown. See Adams, 407 U.S. at 146. Officer Munoz did no more than was required to retrieve the gun. Officer Munoz was entitled to remove Defendant’s handgun, not to discover evidence of a crime, but to permit him and Officer Miller to pursue their investigation without fear of violence. See id. As the Supreme Court observed in Adams, “[T]he frisk for weapons might be equally necessary and reasonable, whether or not carrying a concealed weapon violated any applicable state law.” Id. Accordingly, Officer Munoz’s act of dispossessing Defendant of his handgun subsequent to his seizure was “reasonably related in scope to the circumstances which justified the interference in the first place.” Terry, 392 U.S. at 20. For the foregoing reasons, the order of the district court denying Defendant’s motion to suppress is—AFFIRMED.

aking the second quote first, I would ask which part of the Second Amendment protects the right of a convicted felon to keep and bear a concealed stolen weapon? Larry Pratt of GOA is yellow journalism? No. Maybe red thinks that he's "going negative"? "The People", and "Shall not be infringed" (2nd Amendment). No loopholes there for calling ex-cons names, and then taking their God given inalienable rights. Or is the BOR "yellow journalism"? "Let he who is without sin, cast the first stone".

[sneakypete #9] Remove the "STOLEN",and the Second Amendment is fine with a convicted felon being in possession of a firearm. It used to be routine for criminals leaving prison to be handed their guns back when they were released. It was only after the un-Constitutional GCA was enacted that it became illegal for any free citizen to be in possession of a firearm. Presumably the GCA refers to the Gun Control Act of 1968. The earliest gun control laws concerned concealed carry. The first problem is that you are both just full of shit. The right to keep and bear arms is neither bestowed by God nor the Constitution. The Constitution recognizes capital punishment and you are invited to identify which fictional inalienable God-given right is not taken away by capital punishment. The second problem is that the right to keep and bear arms is protected, but you impute some grotesque definition to the right itself. The third problem is that there are actual laws and court opinions, none of which you cite, because they document that you are just pushing false news or bullshit. As for convicts with guns, it is legally clear under State or Federal law, that their right is rendered forfeit. As for the recent application, Voisine, quoted below, made clear, "Congress enacted §922(g)(9) in 1996 to bar those domestic abusers convicted of garden-variety assault or battery misdemeanors—just like those convicted of felonies—from owning guns." The law expanded to cover garden variety assault or battery misdemeanors. http://law.justia.com/codes/us/2015/title-18/part-i/chapter-44/sec.-922/ [...] (g) It shall be unlawful for any person— (1) who has been convicted in any court of, a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year; (2) who is a fugitive from justice; (3) who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance (as defined in section 102 of the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 802)); (4) who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or who has been committed to a mental institution; (5) who, being an alien— (A) is illegally or unlawfully in the United States; or (B) except as provided in subsection (y)(2), has been admitted to the United States under a nonimmigrant visa (as that term is defined in section 101(a)(26) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(26))); (6) who has been discharged from the Armed Forces under dishonorable conditions; (7) who, having been a citizen of the United States, has renounced his citizenship; (8) who is subject to a court order that— (A) was issued after a hearing of which such person received actual notice, and at which such person had an opportunity to participate; (B) restrains such person from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner of such person or child of such intimate partner or person, or engaging in other conduct that would place an intimate partner in reasonable fear of bodily injury to the partner or child; and (C)(i) includes a finding that such person represents a credible threat to the physical safety of such intimate partner or child; or (ii) by its terms explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury; or (9) who has been convicted in any court of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence, to ship or transport in interstate or foreign commerce, or possess in or affecting commerce, any firearm or ammunition; or to receive any firearm or ammunition which has been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce. [...] A felony is not required. Get a state license to buy pot and federal law renders your right to own a gun forfeit. Illegal aliens and those dishonorably discharged from the military need not apply. See California upholding such a restriction in 1924. It is not some new phenomenon. HOUSER, J. — Defendant was convicted of the offense of having in his possession a pistol after a previous conviction of a felony. He appeals from the judgment and from an order denying his motion for a new trial. [1] The first point made for reversal of the judgment relates to the alleged erroneous admission by the court of certain testimony going to the identification of defendant as the person who had theretofore been convicted of a felony. But inasmuch as the fact of defendant's prior conviction of a felony was established by evidence other than that to which objection is made, the error (assuming it to be such and that it did not result in a miscarriage of justice) was harmless. Prejudicial error is also predicated upon the fact that the prosecution did not show that defendant's admissions were not made under duress or promise of reward. Appellant cites no authority to support such specification of error. [2] However, it may be stated that the rule requiring the prosecution to show that a confession was made freely and voluntarily, without promise of immunity or of reward therefor, does not apply to mere admissions. ( People v. Ford, 25 Cal.App. 388, 418 [ 143 P. 1075].) [3] Furthermore, the record discloses the fact that at no time was any objection interposed to any of the questions asked of any of the several witnesses who testified regarding defendant's admissions; nor was any motion made by defendant to strike out such testimony. In the circumstances appellant's contention cannot be sustained. [4] The statute under which defendant's conviction was had provides, among other things, that "no person who has been convicted of a felony against the person or property of another . . . shall own or have in his possession or under his custody or control any pistol," etc. (Stats. 1923, p. 695.) Appellant urges that in one state a felony might consist in the commission of a designated criminal act, but which identical act in another state might be either a misdemeanor or no criminal act whatsoever; and consequently that the statute is discriminatory and unconstitutional. The statute, however, must be construed in the light of existing laws. Section 17 of the Penal Code defines a felony as a crime punishable with death, or by imprisonment in the state prison, and that statute is necessarily the gauge in this state by which the guilt or the innocence of a defendant with reference to any prior conviction of a felony must be determined. [5] It is next contended by appellant that there is no evidence to sustain the verdict that defendant was guilty "as charged in the indictment" — the specific point being that the indictment charged that the defendant had "in his possession a pistol after previous conviction of a felony"; and that defendant had been "convicted of a felony against the property of another, to wit, of the crime of burglary"; whereas, the evidence as to the defendant's admissions was that he was convicted of receiving stolen property, or "for carrying bombs in his car." The transcript of the proceedings had on the trial shows that an exemplified copy of the judgment on defendant's conviction of a felony in another state was introduced in evidence, from which it appears that the offense for which defendant was convicted was that of burglary. The allegation contained within the indictment is thus supported by the evidence, and the verdict in that particular is therefore legally unassailable. Appellant further urges the unconstitutionality of the Statute under which defendant was prosecuted. It is contended that the statute is a bill of attainder in that in effect, because of an offense committed prior to the passage of such act, it deprives a citizen of a substantial part of his right of self-defense, and that it fixes punishment without judicial trial for a past offense. Appellant also claims that the statute is ex post facto, in that it makes punishable an act otherwise proper and lawful, to wit, the possession of firearms, because prior to the passage of the act a person had been convicted of a felony. A bill of attainder has been defined as "a legislative act which inflicts punishment without a judicial trial"; and an ex post facto law is one which, among other things, may either aggravate a crime, make it greater than it was when committed, or which changes the punishment therefor and inflicts a greater punishment than was provided for when the crime was committed. ( Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. (U.S.) 277 [18 L.Ed. 356, see, also, Rose's U.S. Notes].) [6] That by the terms of the statute in question defendant is not to be punished without a trial is readily apparent. The commission of some offense, to wit, defendant's possession of firearms, must not only be judicially established, but likewise the additional fact of his previous conviction of a felony. Regarding the point that for a past offense, to wit, the crime of burglary, for the commission of which defendant was first convicted, the statute in question seeks to deprive defendant of a substantial part of his right of self-defense — in other words, to punish him for an offense which was committed prior to the enactment of the statute here under consideration — it may be said that legislation of a similar character has heretofore received judicial approval in the case of People v. Smith, 36 Cal.App. 88 [ 171 P. 696], where the statute under consideration provided that any person who (without a license therefor) carried a firearm concealed on his person should be guilty of a misdemeanor, or of a felony, if previously convicted of a felony. It was there held that the act was a reasonable police regulation, not objectionable as class legislation and not ex post facto because providing a heavier penalty for a person charged with an offense who previously had been convicted of a felony. In the case entitled Ex parte Gutierrez, 45 Cal. 429, the validity of a statute which provided in substance that any person convicted a second time of the crime of petty larceny should be deemed guilty of a felony, was considered and the conclusion reached that the act was not ex post facto. The court quoted with approval from Cooley on Constitutional Limitations, as follows: "A law is not objectionable as ex post facto which, in providing for the punishment of future offenses, authorizes the defendant's conduct in the past to be taken into account, and the punishment to be graduated accordingly. Heavier penalties are often provided by law for a second or any subsequent offense than for the first, and it has not been deemed objectionable that in providing for such heavier penalties the prior conviction authorized to be taken into account may have taken place before the law was passed. In such cases it is the second or subsequent offense that is punished, not the first." See, also, People v. King, 64 Cal. 338 [30 P. 1028]; People v. Stanley, 47 Cal. 113 [17 Am. Rep. 401]; Commonwealth v. Graves, 155 Mass. 163 [16 L. R. A. 256, 29 N.E. 579]; and authorities in note to case entitled In re Miller, 34 L. R. A. 398. As is said in Moore v. Missouri, 159 U.S. 673 [40 L.Ed. 301, 16 Sup. Ct. Rep. 179, see, also, Rose's U.S. Notes]: "The increased severity of punishment for a second offense is not a punishment for the same offense a second time." In this connection, see People v. Coleman, 145 Cal. 609 [ 79 P. 283], where the defendant was convicted a second time on a charge of robbery and for which offense the statute provided an increase in punishment over persons convicted the first time of such a charge, and wherein it was held that the increased punishment was not for the prior conviction, but was solely for the aggravation of the second offense, which merited a greater punishment. In the Matter of Application of Rameriz, 193 Cal. 633 [34 A. L. R. 51, 226 P. 914], in which the statute here involved, was under consideration, particularly as affecting the right of an alien to have a firearm in his possession, it is held that the statute is constitutional. It is there pointed out that the right to keep and bear arms is not a right guaranteed either by the federal constitution or by the state constitution, and consequently that the legislature is "entirely free to deal with the subject." The legislature of this state has dealt "with the subject" by a classification of its denizens and its citizens who shall have the right to possess firearms. Such a classification, as is ruled in People v. Smith, 36 Cal.App. 88 [ 171 P. 696], "operates uniformly upon all persons in the same category, and there is a reasonable basis for the classification." Section 246 of the Penal Code declares that "every person undergoing a life sentence in a state prison of this state, who, with malice aforethought, commits an assault upon the person of another with a deadly weapon or instrument, or by any means or force likely to produce great bodily injury, is punishable with death." In the case of People v. Finley, 153 Cal. 59 [ 94 P. 248], it is held that such a classification is unobjectionable and that the statute is constitutional. To the same effect are People v. Quijada, 154 Cal. 243 [ 97 P. 689]; People v. Carson, 155 Cal. 164 [ 99 P. 970]; People v. Oppenheimer, 156 Cal. 733 [196 P. 74]. [7] It therefore becomes apparent that the right of a citizen to bear arms is not acquired from any constitutional provision, and while it may be said that by the operation of the statute under consideration a citizen is deprived of one of his natural rights in that his ability to better defend himself from personal violence if offered will be somewhat lessened, such right is no greater than or different in character from any other natural right possessed by him. It is clear that in the exercise of the police power of the state, that is, for the public safety or the public welfare generally, such rights may be either regulated or, in proper cases, entirely destroyed. Acting within the scope of such power, the legislature, by a proper classification of its citizens, has declared that persons heretofore convicted of a felony shall not possess firearms, and while such citizens are thus deprived of a natural right, in the judgment and discretion of the legislature such deprivation tends directly to the accomplishment of the desired end. As has been indicated by the authorities cited herein, a reasonable basis exists for the classification of citizens of the state in the manner provided by the statute, and there can be no question of the uniformity of its operation upon all persons within the designated class. [8] The rule is unquestioned that in the absence of a clear abuse of legislative discretion, where the subject of the act relates to the exercise of the assumed powers, the courts are unauthorized to interfere with a construction unfavorable to constitutionality. Appellant further urges that the statute is unconstitutional in that it gives to the legislatures of states other than California the power to enact new laws, or to amend existing laws, in effect defining felonies in California, and that the people of this state are powerless to invoke the referendum as to such enactments. The answer to such contention may be found in the fact, as heretofore set forth, that what constitutes a felony is defined by our laws, which would be entirely unaffected by any statute enacted by any other state with reference thereto. [9] It is finally contended by appellant that the statute in question is unconstitutional in that it deprives a person of private property without due process of law. The rule applicable to the facts herein is clearly set forth in 5 California Jurisprudence, page 882, wherein it is said: "All property is held subject to the exercise of the police power, and provisions of the constitution declaring that property shall not be taken without due process of law have no application to cases where such power is lawfully exercised" (citing many California cases). The statement in Matter of Application of Rameriz, 193 Cal. 633 [34 A. L. R. 51, 226 P. 914], is that "private property rights of individuals are required to yield when in conflict with reasonable police regulations." Because of the conclusions heretofore indicated, that the act in question is within the police power of the state, it follows that appellant's contention that by the statute private property is taken without due process of law cannot be sustained. No prejudicial error appearing in the record, it is ordered that the judgment and the order denying the motion for a new trial be and the same are affirmed. - - - - - - - - - - See Voisine v. United States, a 2016 SCOTUS case to verify that illegal carry is not some obsolete concept. Note that a felony is not required. Some misdemeanors act to destroy RKBA rights. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/15pdf/14-10154_19m1.pdf Voisine v. United States, No. 14–10154 579 U.S. ___ Argued February 29, 2016—Decided June 27, 2016 - - - - - - - - - - CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT No. 14–10154. Argued February 29, 2016—Decided June 27, 2016 In an effort to “close [a] dangerous loophole” in the gun control laws, United States v. Castleman, 572 U. S. ___, ___, Congress extended thefederal prohibition on firearms possession by convicted felons to persons convicted of a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence,” 18 U. S. C. §922(g)(9). Section 921(a)(33)(A) defines that phrase to include a misdemeanor under federal, state, or tribal law, committed against a domestic relation that necessarily involves the “use . . . of physical force.” In Castleman, this Court held that a knowing or intentional assault qualifies as such a crime, but left open whether the same was true of a reckless assault. Petitioner Stephen Voisine pleaded guilty to assaulting his girlfriend in violation of §207 of the Maine Criminal Code, which makes it a misdemeanor to “intentionally, knowingly or recklessly cause[ ] bodily injury” to another. When law enforcement officials later investigated Voisine for killing a bald eagle, they learned that he owned arifle. After a background check turned up Voisine’s prior conviction under §207, the Government charged him with violating §922(g)(9). Petitioner William Armstrong pleaded guilty to assaulting his wife inviolation of a Maine domestic violence law making it a misdemeanor to commit an assault prohibited by §207 against a family or household member. While searching Armstrong’s home as part of a narcotics investigation a few years later, law enforcement officers discovered six guns and a large quantity of ammunition. Armstrong was also charged under §922(g)(9). Both men argued that they were not subject to §922(g)(9)’s prohibition because their prior convictions could have been based on reckless, rather than knowing or intentional, conduct and thus did not quality as misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence. The District Court rejected those claims, and each petitioner pleaded guilty. The First Circuit affirmed, holding that “an offense with a mens rea of recklessness may qualify as a ‘misdemeanor crime of violence’ under §922(g)(9).” Voisine and Armstrong filed a joint petition for certiorari, and their case was remanded forfurther consideration in light of Castleman. The First Circuit again upheld the convictions on the same ground. Held: A reckless domestic assault qualifies as a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” under §922(g)(9). Pp. 4–12. (a) That conclusion follows from the statutory text. Nothing in the phrase “use. . . of physical force” indicates that §922(g)(9) distinguishes between domestic assaults committed knowingly or intentionally and those committed recklessly. Dictionaries consistently define the word “use” to mean the “act of employing” something. Accordingly, the force involved in a qualifying assault must be volitional; an involuntary motion, even a powerful one, is not naturally described as an active employment of force. See Castleman, 572 U. S., at ___. But nothing about the definition of “use” demands that the person applying force have the purpose or practical certainty that it will cause harm, as compared with the understanding that it is substantially likely to do so. Nor does Leocal v. Ashcroft, 543 U. S. 1, which held that the “use” of force excludes accidents. Reckless conduct, which requires the conscious disregard of a known risk, is not an accident: It involves a deliberate decision to endanger another. The relevant text thus supports prohibiting petitioners, and otherswith similar criminal records, from possessing firearms. Pp. 5–8. (b) So too does the relevant history. Congress enacted §922(g)(9) in 1996 to bar those domestic abusers convicted of garden-variety assault or battery misdemeanors—just like those convicted of felonies—from owning guns. Then, as now, a significant majority of jurisdictions—34 States plus the District of Columbia—defined such misdemeanor offenses to include the reckless infliction of bodily harm. In targeting those laws, Congress thus must have known it was sweeping in some persons who had engaged in reckless conduct. See, e.g., United States v. Bailey, 9 Pet. 238, 256. Indeed, that was part of the point: to apply the federal firearms restriction to those abusers, along with all others, covered by the States’ ordinary misdemeanor assault laws. Petitioners’ reading risks rendering §922(g)(9) broadly inoperative in the 35 jurisdictions with assault laws extending to recklessness. Consider Maine’s law, which criminalizes “intentionally, knowingly or recklessly” injuring another. Assuming that statute defines a single crime, petitioners’ view that §921(a)(33)(A) requires at least a knowing mens rea would mean that no conviction obtained under that law could qualify as a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.” Descamps v. United States, 570 U. S. ___, ___. In Castleman, the Court declined to construe §921(a)(33)(A) so as to render §922(g)(9) ineffective in 10 States. All the more so here, where petitioners’ view would jeopardize §922(g)(9)’s force in several times that many. Pp. 8–11. 778 F. 3d 176, affirmed. KAGAN, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and KENNEDY, GINSBURG, BREYER, and ALITO, JJ., joined. THOMAS, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which SOTOMAYOR, J., joined as to Parts I and II. - - - - - - - - - - Just for completeness, one recent State case would be 2013 Louisiana case of Draughter. http://www.lasc.org/opinions/2013/13KA0914.opn.pdf [Full opinion at link] FOR IMMEDIATE NEWS RELEASE FROM: CLERK OF SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA The Opinions handed down on the 10th day of December, 2013, are as follows: BY CLARK, J.: STATE OF LOUISIANA v. GLEN P. DRAUGHTER (Parish of Orleans) After reviewing the statue under a strict scrutiny analysis, we hold La. R.S. 14:95.1, as applied to a convicted felon still under state supervision, does not unconstitutionally infringe upon the right to bear arms secured by article I, section 11 of the Louisiana Constitution. The district court’s ruling that La.R.S. 14:95.1 is unconstitutional is reversed. The district court's ruling granting the defendant's motion to quash the bill of information is reversed. This matter is remanded to the district court for further proceedings. REVERSED AND REMANDED. - - - - - - - - - - And here is a concealed carry case from 1840: http://www.constitution.org/2ll/bardwell/state_v_reid.txt State v. Reid, 1 Ala. 612 (1840) 612 ALABAMA. * * * * THE STATE V. REID 1. The act of the 1st of February, 1839, "To suppress the evil practice of carrying weapons secretly," does not either directly, or indirectly tend to divest the citizen of the "right to bear arms in defence of himself and the State;" and is, therefore consistent with the 23d section of the 1 Art. of the constitution. [...] COLLIER, C. J.--By the first section of the act, "to suppress the evil practice of carrying weapons secretly," [Acts of 1838-9] it is enacted, "that if any person shall carry concealed about his person, any species of fire arms, or any Bowie knife, Arkansas tooth pick, or any other knife of the like kind, dirk, or any other deadly weapon, the person so offending, shall on conviction thereof, before any court having competent jurisdiction, pay a fine not less than fifty nor more than five hundred dollars, to be assessed by the jury trying the case; and be imprisoned for a term not exceeding three months, at the discretion of the judge of said court." [...] The bill of rights was doubtless induced by the high perogative claims of the Stuarts, even after the restoration of Chas. the II., but more especially by the extraordinary assumptions of Jas. the II., by which he attempted to assail the liberties and religion of the people, and to render inefficient the enactments of Parliament, by the exercise of a dispensing power. The bill of rights, among other things confirms the declaration of rights, to which the Prince of Orange yielded his assent in the presence of both houses of Parliament, upon ascending the throne. That instrument recited the illegal and arbitrary acts committed by the late King, and declared almost in the terms of the recital, that such acts were illegal. The evil which was intended to be remedied by the provision quoted, was a denial of the right of Protestants to have arms for their defence, and not an inhibition to wear them secretly. Such being the mischief, the remedy must be construed only to extend so far as to effect its removal. We have taken this brief notice of the English statute, as it may serve to aid us in the construction of our constitutional provision, which secures to the citizen the right to bear arms. [...] The question recurs, does the act, "To suppress the evil practice of carrying weapons secretly," trench upon the constitutional rights of the citizen. We think not. The constitution in declaring that, "Every citizen has the right to bear arms in defence of himself and the State," has neither expressly nor by implication, denied to the Legislature, the right to enact laws in regard to the manner in which arms shall be borne. The right guarantied to the citizen, is not to bear arms upon all occasions and in all places, but merely "in defence of himself and the State." The terms in which this provision is phrased seems to us, necessarily to leave with the Legislature the authority to adopt such regulations of police, as may be dictated by the safety of the people and the advancement of public morals. The statute of 1 Wm. and M. while it declares the right of the subject, it refers to Parliament to determine what arms shall be borne and how; while our constitution being silent as to the action of the Legislature, does not divest it of a power over the subject, which pertained to it independent of an express grant. [...] - - - - - - - - - - Notably, the Right to Keep and Bear Arms descended from the English Common Law and was not passed down by a guy with a white beard descending from a mountain with a stone tablet inscribed by God Himself.

Yes, that would be the one that Charleston Heston asked LBJ to sign. Convicts were those guys on the chain-gang cutting weeds along the side of the road, being guarded with shotguns. They were convicts serving a jail sentence. Once they had served their time and were released, they were known as ex-cons. The term felon was virtually unheard of. Heston, for the Record by Robert W. Lee On May 3rd of last year, actor Charlton Heston was elected to the board of directors of the National Rifle Association (NRA) during its national convention in Seattle. Two days later, the 76-member board voted to make Heston NRA first vice president over incumbent Neal Knox, a former NRA chief lobbyist who heads the Maryland-based Firearms Coalition. The Associated Press reported at the time, "Heston’s election ran against a long tradition of two, one-year terms for each of the top three officers, with the second vice president moving up to first vice president, and then to president." One Heston backer on the board told AP: "Certainly this is an appropriate time that we not adhere to that tradition. I think the Lord’s given us a prophet and we ought not to turn our backs on what the Lord has given." Heston is best known for his role as Moses in the 1956 Hollywood classic The Ten Commandments. As first vice president, Heston is currently on track to become NRA president in June. However, recent revelations about Heston’s role in promoting President Lyndon Johnson’s 1968 gun control legislation, and his involvement in an anti-gun group formed at the time by fellow actor Tom Laughlin, have become potentially serious speed bumps on the popular Hollywood figure’s road to higher NRA office. Help From Hollywood The controversy erupted after the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library released documents confirming that Heston and a handful of colleagues worked closely with White House insiders to persuade the American public and Congress to support a bill to prohibit the interstate shipment of rifles, shotguns, and handgun ammunition, and to restrict out-of-state purchases of rifles and shotguns. President Johnson had already signed into law the 1968 omnibus crime control bill, which included sundry curbs on handguns. One provision banned the interstate mail-order sale of handguns, but the President did not think that ban went far enough, and so he proposed new gun legislation targeting shotguns and rifles. On June 10, 1968, the House Judiciary Committee scuttled the proposal. The next day, the President issued a brief statement expressing his "bitter disappointment" and declaring that "there is no excuse whatsoever for failure to act to prohibit the interstate mail-order sale of rifles." He urged the Judiciary Committee to "promptly reconsider this shocking blow to the safety of every citizen in this country." On June 12th, Lawrence Levinson, deputy special counsel to the President, sent a memo to Heston at his home in Beverly Hills. Claiming that the interstate mail-order ban in the crime bill "is only a half-way measure" since it "covers only handguns — but fails to include shotguns and rifles," Levinson briefly outlined the President’s proposal to also place rifles under the gun control tent. That same day, Levinson explained in a memo to White House staffer Charles Maguire: At the President’s suggestion, Jack Valenti [president of the Motion Picture Association of America and former special assistant to LBJ] has agreed to hold a luncheon in Los Angeles next Monday, June 17th, at noon (PDT), at which a number of famous movie actors — particularly those who play cowboys — will speak out in favor of the President’s gun control legislation. For this luncheon, we need two pithy, one-page statements which will be read by two of the "cowboys" (probably Charlton Heston and John Wayne), supporting the President’s Gun Control Bill. May I suggest that Hardesty do one and Harry Middleton do the other, with you to supply some polish. There is no further reference to the luncheon in documents released to date. But on June 18th, Levinson sent a memo to the President outlining a far more important project: Through Jack Valenti’s good work, five movie actors will appear on the Joey Bishop show at 11:30 tonight on Channel 7 to support strongly your gun control proposal. The actors involved are Gregory Peck, Charlton Heston, Hugh O’Brian, James Stewart, and Kirk Douglas. They will read a very tough statement which we prepared here applauding your action in calling for strict gun control curbs. A Telling Statement Also on June 18th, Dick McKay of the Beverly Hills public relations firm Rogers, Cowan & Brenner, wrote to presidential assistant Joseph Califano about the project’s progress: Enclosed are three copies of the final version of the statement released to the Associated Press and United Press International here in Los Angeles today. Hugh O’Brian asked me to send these to you. Hugh and I met at his home last evening and I wrote a lead-in which I considered newsworthy but he felt that it was too professional and, depending upon what results are eventually achieved, he may have been right. Instead, the lead-in was something as simple and direct as "We, Kirk Douglas, James Stewart, Hugh O’Brian, Gregory Peck, Charlton Heston, wish to make the following statement...." Charlton, Gregory, and Hugh personally planted this statement with the bureau chiefs at AP and UPI. They were greeted warmly and Hugh reports that, based on the reception and ensuing conversation, the results should be excellent. The AP also photographed the trio. McKay then described the steps intended to deceive the public about behind-the-scenes orchestration of the enterprise: "These three stars felt that it might be detrimental for their purposes to have a press agent along with them so I merely set up all the details, which they followed through on their own. I think that their reasoning may be correct that their whole plan may get better treatment if there is, apparently, not a public relations man involved. Naturally, from a professional point of view there are very few instances where I would agree with such thinking." On June 20, 1968, Califano wrote in a memo to President Johnson: I thought you might be interested in the attached statement which Hugh O’Brian read on the Joey Bishop Show last Tuesday. This was a statement subscribed to by Kirk Douglas, James Stewart, Gregory Peck and Charlton Heston and has been widely circulated throughout the country. The statement "subscribed to" by Charlton Heston and his associates included the following: • "Our gun control laws are so lax that anyone can buy a weapon." • "We share the conviction that stronger gun control legislation is mandatory in this tragic situation." • "The Congress has recently given us some protection against pistols in the wrong hands. But that’s not enough … not nearly enough. The carnage will not stop until there is effective control over the sale of rifles and shotguns." • "For many long months, the President of the United States has asked the Congress to pass a such a law … but the Congress will not listen unless you, the voter, speak out.... Unless the people of this country rise up and demand that the Congress give us a strong and effective gun control law." After summarizing the President’s proposed legislation, and citing the House and Senate bill numbers, the statement declared: "We urge you, as a responsible, sensible, and concerned citizen, to write or wire your senator and congressman immediately and demand they support these bills." Gun Control Diehard The effort had the intended impact. On July 14th the House approved the measure by a vote of 305 to 118. On September 18th, the Senate followed suit by a tally of 70 to 17. As described by the 1969 World Book Encyclopedia Yearbook, "On October 22 [1968], the first major gun control law in 30 years was enacted. It was the strongest gun control legislation in the nation’s history." As finally approved, the legislation: • Outlawed the mail-order sales of all rifles, shotguns, and ammunition, except between licensed dealers, manufacturers, and gun collectors. • Banned the sale of rifles, shotguns, and handguns to persons under 21 years of age. • Banned direct sales of guns to out-of-state residents unless the state involved specifically authorized its citizens to buy guns in adjoining states. In a related development that year, actor Tom Laughlin (best known for his later roles in "Billy Jack" movies) formed an anti-gun movement called "Ten Thousand Americans for Reasonable Gun Control." Initially, it attracted the support of many movie and television personalities, but most subsequently deserted the group. The NRA’s American Rifleman magazine for October 1968 quoted Laughlin as stating: "They were all hepped up for 2 weeks. The commitment couldn’t last any longer than that. It’s frightening to me." But not everyone jumped ship. As reported by the American Rifleman, "Laughlin cited as diehards who stuck with his anti-gun movement a ‘little more than a handful’" — including Charlton Heston. Going Mainstream Heston has expressed a desire to move the NRA into the political "mainstream." He has downplayed the significance of the Brady waiting-period law, claiming not only that it is "cosmetic" and "meaningless," but that "I don’t care if they keep the Brady Act forever." During a May 9, 1997 interview on San Francisco radio station KGO, Heston, who had just been elected NRA first vice president the previous day, was asked if he would try to get "the right-wing folks off the [NRA] board and out of the picture." He replied, "That’s certainly the intention, and I think it’s highly doable." On March 6th of this year, the NRA issued a press release defending Heston and labeling as "a few minor dissidents" those who have expressed concern about his support of LBJ’s gun control agenda and involvement in the Laughlin group. Such critics, the NRA claimed, "have attempted to smear and impugn" his integrity. The bulk of the release consisted of 11 commendable gun-related quotations excerpted from Heston speeches and media appearances during 1997. However, the Johnson Library documents were not mentioned, and the vexing questions they raise went unanswered. The release concluded: "In response to those self-serving dissidents who have criticized him, Mr. Heston said simply, ‘I stand by my record.’ We, too, stand on that record along with nearly three million NRA members committed to preserving our Second Amendment freedoms." Dismissing as "self-serving dissidents" those who are justifiably concerned about the reliability of Heston’s pro-gun commitment, while ignoring the important questions raised by the crucial role he played in the passage of anti-gun legislation which the NRA vigorously opposed, is likely to fuel rather than dissipate the controversy. Gun advocates, including more than just "a few minor dissidents" within the NRA itself, are anxious to know the extent to which Heston’s position today differs, deep down and not just rhetorically, from that which he espoused earlier. Beyond that, there is the question of whether or not a "mainstream" NRA purged of its "right-wing" element can effectively keep gun-control zealots at bay. © Copyright 1994-2000 American Opinion Publishing Incorporated https://thefiringline.com/forums/showthread.php?t=28430

[nolu chan #34] Presumably the GCA refers to the Gun Control Act of 1968. [sneakypete #35] Yes, that would be the one that Charleston Heston asked LBJ to sign. yada, yada, yada. Logical conclusion: it was not until 1968 that it became illegal for any free citizen to be in possession of a firearm. In reality, it became illegal for many free citizens to be in possession of a handgun before Charlton Heston was born. PROBLEMS: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sullivan_Act [...] In addition to handguns, the Sullivan Act prohibits the possession or carrying of weapons such as brass knuckles, sandbags, blackjacks, bludgeons or bombs, as well as possessing or carrying a dagger, "dangerous knife" or razor "with intent to use the same unlawfully". Violation of any of the prohibitions is a felony. [...] In New York State, apart from New York City, the practices for the issuance of concealed carry licenses vary from county to county. In New York City, the licensing authority is the police department, which rarely issues carry licenses to anyone except retired police officers, or those who can describe why the nature of their employment (for example, a diamond merchant who regularly carries gemstones; a district attorney who regularly prosecutes dangerous criminals, etc.) requires carrying a concealed handgun. Critics of the law have alleged that New Yorkers with political influence, wealth, or celebrity appear to be issued licenses more liberally. In recent years, the New York Post, the New York Sun, and other newspapers have periodically obtained the list of licensees through Freedom of Information Act requests and have published the names of individuals they consider to be wealthy, famous, or politically connected that have been issued carry licenses by the city police department. Concealed weapons have a long history of being excluded, even by state constitution. In State v. Speller, 86 N.C. 697 (1882) We concede the full force of the ingenious argument made by counsel upon this point, but cannot admit its application to the statute in question. The distinction between the "right to keep and bear arms," and "the practice of carrying concealed weapons" is plainly observed in the constitution of this state. The first, it is declared, shall not be infringed, while the latter may be prohibited. Art. I, sec. 24. As to the surest inhibition that could be put upon this practice deemed so hurtful as to be the subject of express mention in the organic law of the state, the legislature has seen fit to enact that at no time, and under no circumstances, except when upon his own premises, shall any person carry a deadly weapon concealed about his person, and it is the strict duty of the courts, whenever an occasion offers, to uphold a law thus sanctioned and approved. But without any constitutional provision whatever on the subject, can it be doubted that the legislature might by law regulate this right to bear arms--as they do all other rights whether inherent or otherwise--and require it to be exercised in a manner conducive to the peace and safety of the public? This is as far as this statute assumes to go. It does not say that a citizen when beset with danger shall not provide for his security by wearing such arms as may be essential to that end; but simply that if he does do so, he must wear them openly, and so as to be seen by those with whom he may come in contact. The right to wear secret weapons is no more essential to the protection of one man than another, and surely it cannot be supposed that the law intends that an unwary advantage should be taken even of an enemy. Hence it takes no note whether the secret carrying be done in a spirit of foolish recklessness, or from a sense of apprehended danger, but in either case declares it to be unlawful. Indeed, were there any difference made, we might expect it to be (p.701) against one who felt himself to be under some pressure of necessity, since in his case the mischievous consequences intended to be avoided, might the more reasonably be anticipated. And it would be a strange passage in the history of legislation to enact that it shall be unlawful for any person to carry concealed weapons about his person, except when it may be supposed he shall have occasion to use them. This disposes of the defendant's last exception. If the fact that he had been previously assaulted could furnish no justification, or in any way affect the issue to be tried by the jury, it was certainly proper to exclude the evidence with regard to it. No error. Affirmed.

#42. To: nolu chan, sneakypete (#38)

The Sullivan Act is a gun control law in New York State that took effect in 1911. Upon first passage, the Sullivan Act required licenses for New Yorkers to possess firearms small enough to be concealed. Possession of such firearms without a license was a misdemeanor, and carrying them was a felony. Pete it looks like Mr. Chan was correct.

Wrong again! I wrote those words in #35.

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest On the other hand, there is reason for pause with Judge Gorsuch's record. Judge Gorsuch joined in one opinion, United States v. Rodriguez, 739 F.3d 481 (11th Cir. 2013), which causes us to have some concern about his understanding of the relationship between the government and an armed citizenry. To be fair, Judge Gorsuch did not write the Rodriguez opinion – his colleague, Judge Bobby Baldock, was the author. Nevertheless, Judge Gorsuch joined the opinion. He could have filed a principled dissenting opinion, or even a concurring opinion agreeing only in the judgment.

To be sure, Rodriguez did not raise a Second Amendment claim before the court, and the court cited various Fourth Amendment cases to justify its bad decision.

US v. Rodriguez, 739 F.3d 481 (10th Ct. App. 2013)

Date: December 31, 2013

Defendant: Rodriguez

#2. To: nolu chan, redleghunter (#1)

Rather than accept the yellow journalism characterism of the court opinion

#34. To: hondo68, sneakypete, redleghunter (#2)

[hondo68 #2: "The People", and "Shall not be infringed" (2nd Amendment). No loopholes there for calling ex-cons names, and then taking their God given inalienable rights. Or is the BOR "yellow journalism"?

"The People", and "Shall not be infringed" (2nd Amendment). No loopholes there for calling ex-cons names, and then taking their God given inalienable rights. Or is the BOR "yellow journalism"?

§922. Unlawful acts

People v. Camperlingo, 69 Cal.App. 466, 473, 231 P. 601, 604 (1924)

VOISINE ET AL. v. UNITED STATES

Supreme Court of Louisiana

NEWS RELEASE #070

2013-KA-0914 The State v. Reid.

#35. To: nolu chan, sneakypete, buckeroo, Deckard (#34)

(Edited)

Presumably the GCA refers to the Gun Control Act of 1968.

The following article first appeared in the April 13, 1998 issue of The New American magazine. www.thenewamerican.com

---------------------------------------------

#38. To: hondo68, sneakypete (#35)

[sneakypete #9] It was only after the un-Constitutional GCA was enacted that it became illegal for any free citizen to be in possession of a firearm.

The Sullivan Act is a gun control law in New York State that took effect in 1911. Upon first passage, the Sullivan Act required licenses for New Yorkers to possess firearms small enough to be concealed. Possession of such firearms without a license was a misdemeanor, and carrying them was a felony.

The exception taken to the charge of the court, as we are told at the bar, is based upon the supposed unconstitutionality of the statute under which the defendant is prosecuted, and the lack of lawful power in the legislature to deprive a citizen at any time of his right to bear arms, and especially when needed to repel a threatened assault from which great bodily harm might reasonably be apprehended

Replies to Comment # 38. [sneakypete #9] It was only after the un-Constitutional GCA was enacted that it became illegal for any free citizen to be in possession of a firearm.

#43. To: nolu chan, sneakypete (#38)

[sneakypete #35] Yes, that would be the one that Charleston Heston asked LBJ to sign.

End Trace Mode for Comment # 38.

[Home] [Headlines] [Latest Articles] [Latest Comments] [Post] [Mail] [Sign-in] [Setup] [Help] [Register]